A couple of weeks ago I posted this little ditty about how to cold boot your Mac remotely, and one of the options nestled in the screenshot I included with that post was the intriguing “Wake for network access” checkbox.

It’s an option that I’ve mostly avoided paying any attention to over the years, because the computers I mostly tend to deal with are ones that are seldom (if ever) actually turned off. There are lots of reasons why this is the case, but they tend to fall into the two general buckets of This Computer Needs To Stay On Because People Are Getting Files From It, and the equally capitalized This Computer Needs To Stay On Because People Are Getting Services On It. The idea of needing to wake a computer remotely seemed a fringe issue at best, but oh how the wheel turns and time makes fools of us all etc etc.

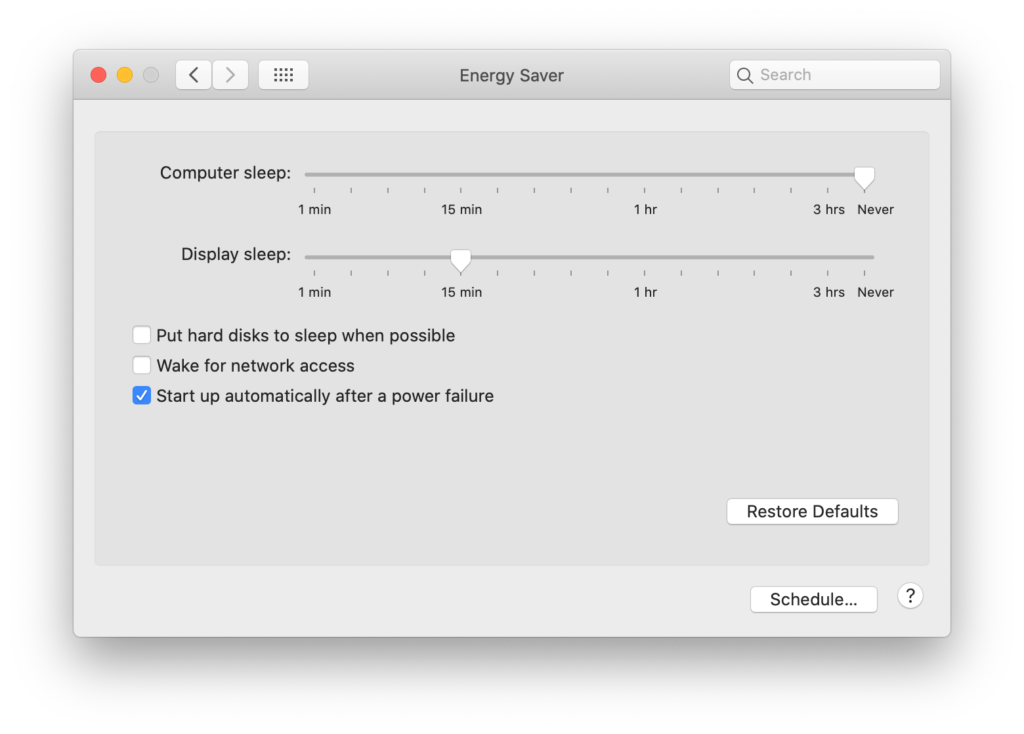

We’re living in a world where remotely tinkering with non-servers is starting to be more of a pressing issue and a requirement than a suggestion. And there are ways of dealing with those kinds of requirements that aren’t immediately obvious. If you put the average, intelligent person in front of a screen with a checkbox marked “Wake for network access” then chances are they’d look up at the fact that the preference pane that the option is nestled in, note that it’s the Energy Saver pane, and come to the logical conclusion that if this is a place that controls when your computer goes to sleep and there’s an option there for something to do with waking over a network then it’s not a huge or illogical conceptual jump to decide that that if their computer was asleep and you tried to connect to it over the network then the computer would wake up.

This, it turns out, is absolutely true. And – in a more precise and accurate sense – an utter, utter lie. It’s entirely possible to wake your computer remotely, but there’s a specific way of doing it that isn’t immediately obvious and that isn’t ever really called out, and that way is by the implementation and use of a Magic Packet.

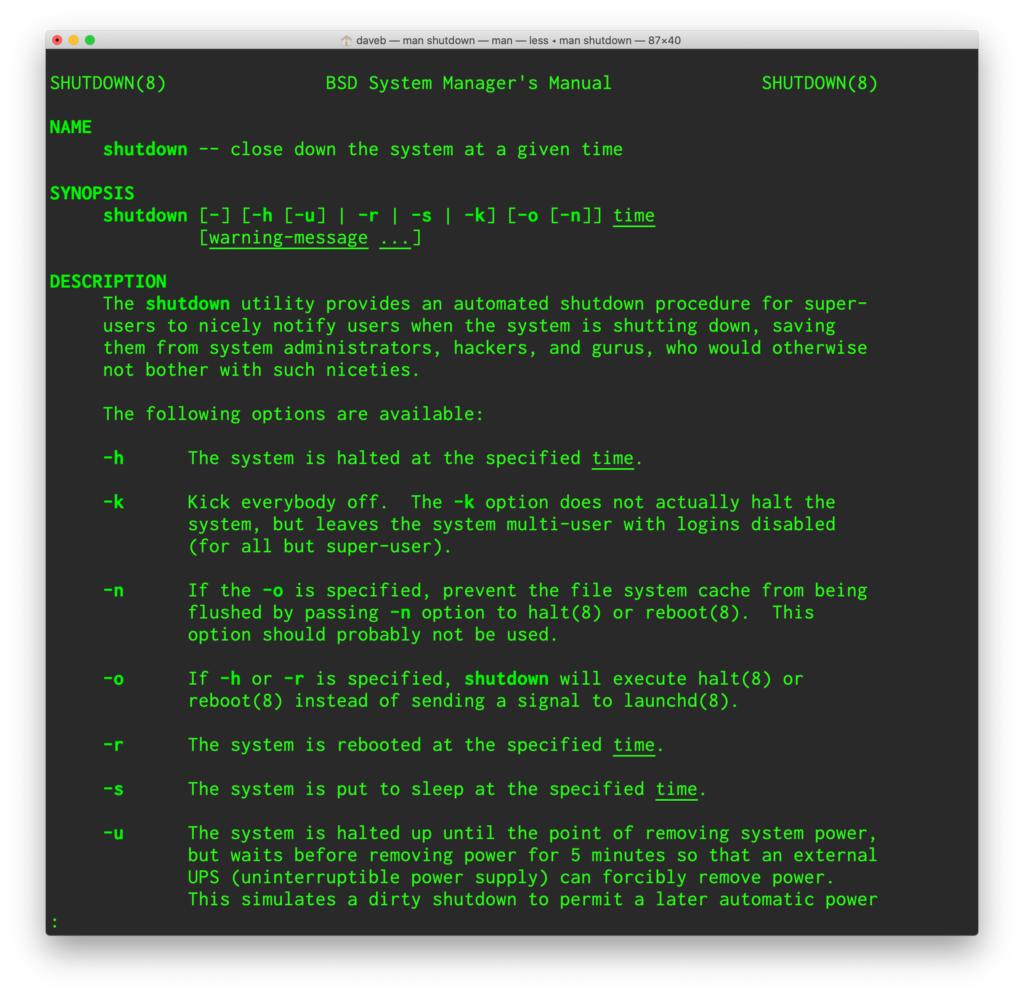

Okay, I should probably explain what a Magic Packet is. I could also call it a magic packet, sans capitalization, but that’s less fun, and if you’re going to reference supernatural capabilities in your IT doublespeak then you might as well lean into it. A Magic Packet is a specially-crafted network packet that contains the MAC address of the computer that it’s intended to reach, sent out over UDP to port 0, 7 or 9. It’s a highly targeted, highly specific finger prod to the sleeping computer that only that computer will respond to, and if you want to make one on your Mac then you have to jump through a hoop or two.

Firstly, you need a way to make a Magic Packet. This is probably unsurprising for anyone who’s read more than half a dozen of my posts, but I’m going to use homebrew to install a package to create and send said Magic Packet, thus:

brew install wakeonlan

Secondly, you’ll need some information about the computer you’re crafting the Magic Packet for – notably its IP address, the port number you’re aiming for, and its MAC address. The port number is 9 on macOS (at least, it is in every case I’ve seen so far, and if that doesn’t work you can try ports 0 and 7), and the command should be formatted something like this:

wakeonlan -i 10.0.0.1 -p 9 12:34:56:78:ab:cd

Plug that into the Terminal on the computer you’re trying to connect from, and all things being equal it’ll find its way to the targeted computer and raise it from it’s slumbers…