I wrote last time about how updates to Operating Systems never fail to arouse the deepest passions in the bosoms of their users. Tears of joy vs gnashing of teeth, wearing of sackcloth and so forth. Any time you take something fundamental that people build their workflow off and make any kind of change you’re always going to court disaster and heartbreak, but very, very occasionally there’s a change that people are pretty much universally going to applaud.

Sometimes those things are the result of careful design or listening to the needs of the clamoring public. Sometimes those things are happy mistakes. Sometimes those are things that are just in the spirit of trying something new. And sometimes – just once in a while – they’re the result of looking at a prior change and then rolling that back. Big Sur (as of it’s current Public Beta 10) has a bunch of all of those – both large and small – but the one that I’m most excited-slash-relieved about is probably the most trivial: they fixed Show Original.

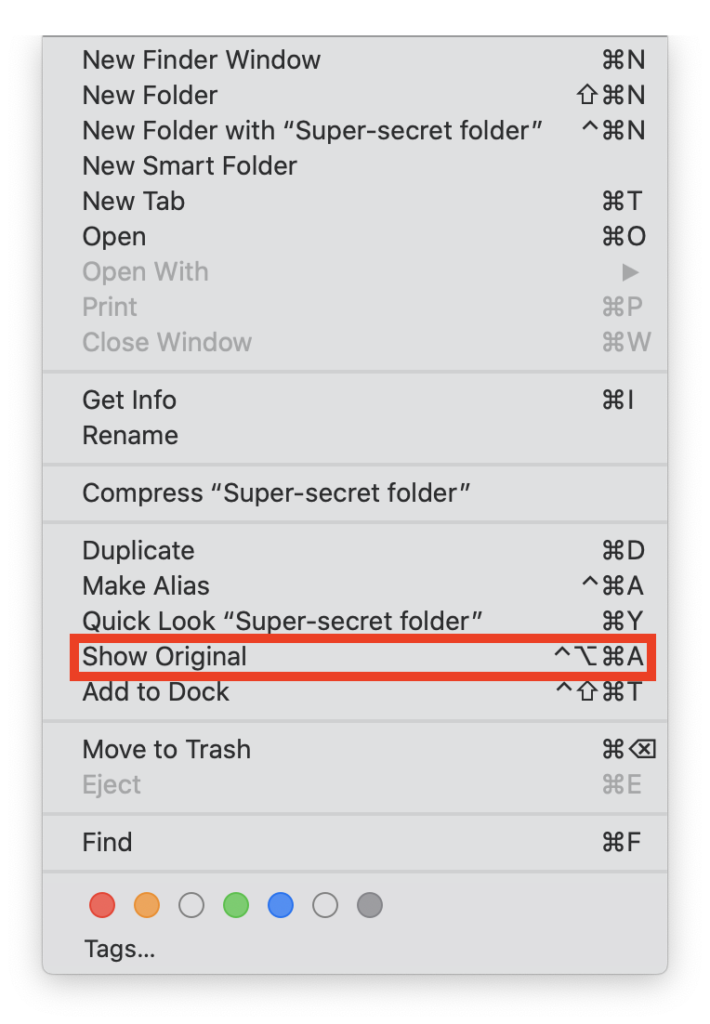

For anyone who doesn’t use file aliases (and yes, I’m including directories as being files because we could get into a useless syntactic discussion about that but this is my blog, dammit) an alias is a link to a file that lives at an alternate location. Maybe – like me – you have a bunch of folders that you regularly use but that you don’t want to have actually live on your Desktop. Or on your computer at all, for that matter. Maybe they live on an external drive, or a file server, or a NAS. There are lots of reasons for going that route, after all; shared access, retention, backup strategies – but it’s also just a lot more convenient to have the things you want to access close at hand. Now and again, though, you might want to know where the original file is or navigate to it, and in macOS Catalina that meant either scouring Finder menus or memorizing a bunch of keystrokes designed to break your own left hand. Here, this is what I mean:

I mean, look at that key combination. It’s… well, I don’t really have the words. “Bonkers” seems like a decent shot, though. I think what I’m aiming for is something more puzzling than rage-inducing; after all, decisions on this kind of thing aren’t made by accident because they are, after all, decisions. At some point, some bright, eager software engineer scratched his or her chin and said “You know what? There are too many people who are inadvertently attempting to find aliases of their files, and yes, Bob, I know that we’re talking about a fringe number of cases where someone has to select the alias in the Finder and then hit a keystroke or two to reveal the location of the individual file, but it’s still a risk that’s not worth taking, dammit. After all, nobody in their right mind wants to live in the kind of world where you can puncture the fragile illusion of how the file system works. Something must be done, so I think we should immediately implement a series of keystrokes that are difficult if not torturous to perform so that this eventuality never comes to fruition and so that we can sleep at night secure in the knowledge that we’ve demonstrably done something with our time. Sushi, anyone?”

(At least, I’m guessing that’s more or less how it went based on the small amount of time I’ve spent working for huge corporations and the much, much smaller amount of time I’ve spent at Infinite Loop eating Sushi at Caffe Macs.)

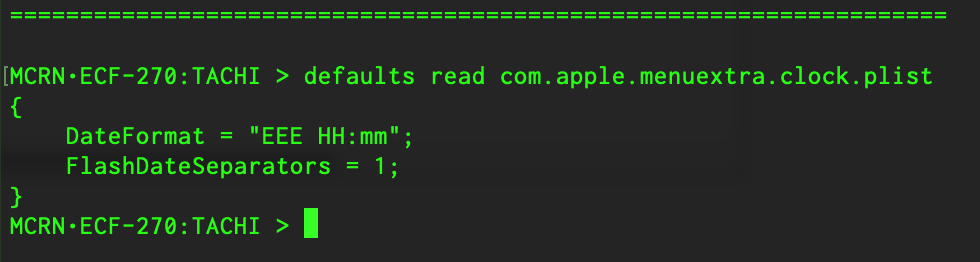

Just to make really, really sure that this was as unpleasant as possible, they then decided to use all the modifier keys on the keyboard that I – David Ball – have a hell of a time remembering.

Now, I might be alone in this one, and if that’s the case then – if you’ll pardon awkward metaphors – I’ll hold my hand up and take it on the chin. I’ve been working with Apple and macOS in a professional capacity for the better part of a quarter of a century, and while I’m comfortable with what the Command key looks like (⌘), the other two – Option (⌥) and Control (⌃) are things that I have to sneak a peek at the keyboard for (which in the case of Control is particularly inexcusable because I’m always in the Terminal and am constantly hitting that key on a daily – if not hourly – basis). And so, this is me; and if I – someone who ostensibly knows his way around the macOS – am reduced to making confused, whining noises when trying to find the original of an alias then it’s a decent bet that other people are, too.

Of course, adding insult to injury is that the non-modifier key involved is the “A” key, which is smack dab in the middle of the three modifiers and up two rows, so no matter whether you hit the modifiers with whichever combination of fingers you’d care to go with you either end up twisting a finger around or doing some kind of wrist contortion to hit all four keys at once. It’s hard to take this as anything other than some kind of deliberate assault (albeit, a low-stakes one).

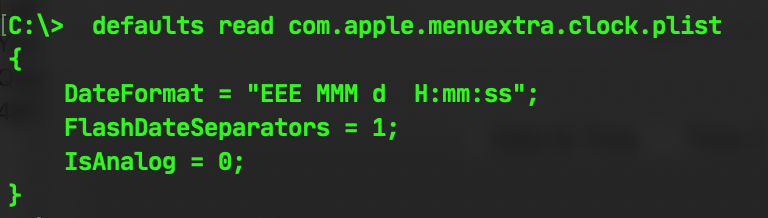

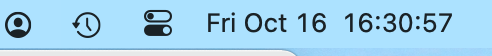

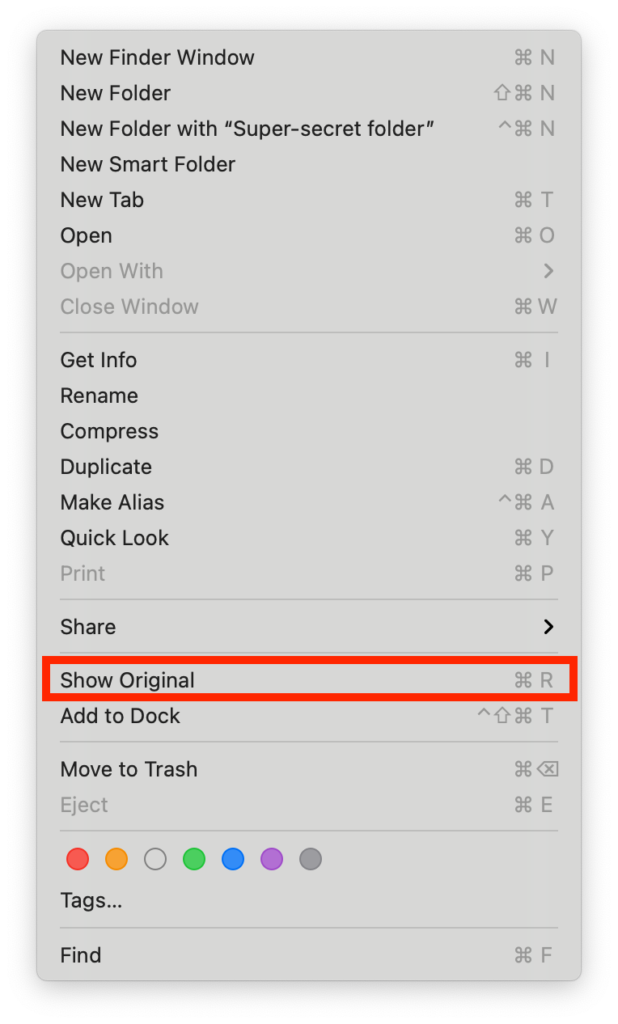

It didn’t use to be this way. Prior to macOS Catalina you could hit Command-R in the Finder while selecting an alias, which was simple and easy to mnemonically accommodate (“Command-R means… find ‘riginal?), and thankfully this is something that they’ve re-implemented in Big Sur, thus:

So, all is right with the world. We can all go back to our daily lives secure in the knowledge that this travesty has been resolved, that this great iniquity has been cast aside, and that once again we are free as a people to stand in the light of the sun and eat breakfast under newer, better skies. Okay, there might be the slightest hint of an over-reach in that sentiment; after all, many other things are still in assorted states of brokenness, but the point has enough legs to stand on (albeit in a highly qualified fashion).

The lesson here is not that you need to make a lot of changes to the way that you think about how operating systems work; it’s that there’s value in doing something right the first time, then having the clarity to appreciate and acknowledge that value. I’m not mad because Apple changed a keystroke combination that, let’s face it, most people would go to the appropriate pull-down menu to access anyway. I mean, that’s a fairly small hill to die on. No, the thing that concerns and annoys me is that while most good designers make decisions based on forethought and conceptual understanding, there’s always the pitfall of thinking that you’re going to do something better, and that the work that has been done before lacks value and needs to be remedied.

And it’s not something unique to Apple. I’ve seen that tendency in code that I’ve written and revisited, and I imagine that a lot of people in my shoes have had the same experience. Sometimes you’re so eager to improve something that you fall into the trap of thinking that everything you touch needs to be changed, and you end up throwing up roadblocks to productivity that didn’t need to be put there. You can measure twice and cut once as often as you like, but if the thing doesn’t need to be cut at all? Well. The next best thing you can do is to have the humility to undo your mistakes.