This is, believe it or not, the busiest part of the year if you’re an IT consultant. There are excellent reasons for this; businesses are generally keen to close out budgets, or make purchases and roll out products prior to the end of the tax year, or even just feel the universal urge to do whatever it takes to tie a neat knot around the year and go into the next one loaded for bear. The practical upshot of that is that I haven’t written anything for this thing for a while because I’ve been far too busy running around and actually working (which is exactly the kind of problem you want to have if you’re me).

Still, I have a running list of things I wanted to touch on because I think they’re interesting and because this blog is as much as anything else a resource that I can go back and look at when I need to remember some piece of syntax that gets shoved out of my aging cranium to make space for something more critical. One of those things concerns my first love (at least in a professional sense), which is homebrew.

(Okay, honorary shout-out to Synology as my other first love. It’s the weirdest, nerdiest form of polygamy.)

Homebrew is fabulous. I like to support it financially when I can because it’s a simple and effective way of putting together tools that enable me to do my job. I mean, sure, there are other ways of building programs and tools that are perfectly functional, but if IT consultants are plumbers then homebrew is an organization that just hands out wrenches for free. You can’t beat that value, and you’d be a fool to try. Still, now and again open-source tools run afoul of the rest of the world, and it can be jarring to reach for a wrench only to find that – against all expectation – it’s not where you left it.

I’m referring in this case to YouTube-dl, and the recent debacle over it’s equally recent removal and reinstatement on GitHub. You can read that link, or I can outline the rough lines of the story, which is pretty simple. YouTube-dl is a tool that you can feed a streaming video URL to, and which will then process that URL to extract the video and audio feeds and download them to your computer. Despite the name it’s a tool that works on, well, basically every service that streams non-DRM encoded video, and while it’s (fairly predictably) used to scrape video content from the internet that providers may not want scraped, it also has a raft of legitimate and fair use applications. I work with educators who’ll use it to pull academically-licensed video down to machines for presentations and research purposes, for example.

Still, the problematic use cases of the tool (notably the bit about being capable of illegally downloading and saving copyrighted music and video) ran afoul of the RIAA, who complained to GitHub that they were hosting a tool that was in contravention of copyright law, and in turn GitHub pulled the tool and left a lot of proverbial plumbers without proverbial wrenches.

Fortunately, all parties saw sense and restored Youtube-dl within days, but during the outage I had to do some very specific poking around about how to find and build the tool from non-GitHub resources, and in turn how to use it to manually select video and audio formats, which turned out to be rather interesting.

As anyone who’s uploaded video to YouTube will tell you, it’s not simply a process of lobbing it a file and then going and having a cup of tea while it puts all the ones and zeroes onto a webpage for your delectation and delight. That’d be convenient, but there’s more to it; YouTube is accessed by all kinds of client computers and devices over all kinds of connections, and as such it likes to have a lot of different versions of those video and audio files to serve out to those computers and devices. After all, if I’m watching a video on my iPhone on an LTE connection and the only video they can send my iPhone is the same full-resolution 4k file they’d send to my desktop wired to fiber then I’d stand in the rain watching the thing spool for a very long time while I asked myself whether I really needed to spend thirty minutes waiting to watch a cat video, and whether I should have considered my life choices with greater attention to time-management and the ownership and use of an umbrella.

Fortunately, YouTube-dl makes it easy to look at all the different versions of audio and video streams associated with a YouTube video, and then allows you to pick and choose which versions you’d like to download. Let’s start with a classic educational staple – Dr. Richard P. Astley’s rendition of the immortal classic “I Shall Never Give You Up.”

The YouTube URL for this is:

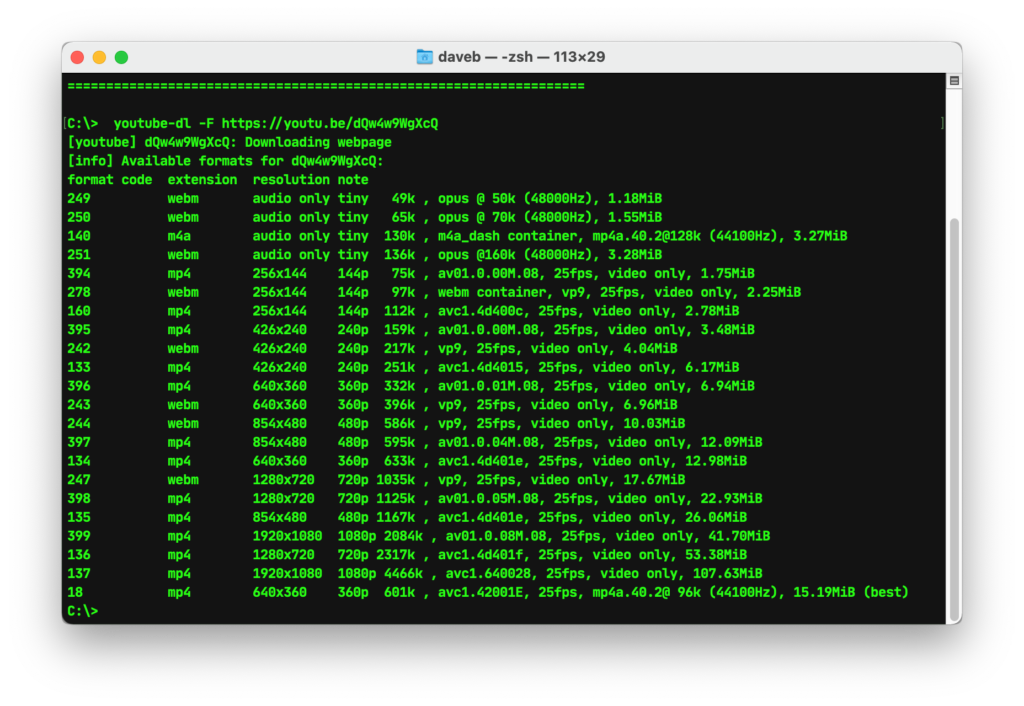

If you copy that URL and paste into YouTube-dl while invoking the -F option then you’ll get this impressive looking list:

From looking at that list, we can see that there are four audio-only formats, seventeen video-only formats, and one combo option right at the very end. YouTube takes this menu, looks at your connection and the device you’re using, and then selects the best options from the list, but we can use YouTube-dl to make our own choices by invoking the -f option. Let’s say we want to download the highest-possible quality video file (the 1080p mp4 option – number 137 on the list ) and the worst quality audio file (the 49k webm option – number 249 on the list). To download that using YouTube-dl you’d use the command:

youtube-dl -f 137+249 https://youtu.be/dQw4w9WgXcQ

The output will look something like this:

…et voila – you now have a copy of the file in the home folder on your computer.

All talk of plumbers and nonsense aside, I can kind of see the concern about the use of tools like Youtube-dl. It is, after all, a tool that can be used for both legitimate and illegitimate use alike, and how it’s wielded is largely a matter of personal judgment and policy. On a practical level, I suspect that the prospect of it being used wholesale as a mainstream piracy tool is limited by the fact that unless you want to go spelunking into video and audio formats a default invocation of the command will feed you a pretty good copy of a video that’s really no better than just viewing the content for free on the internet. Further, if you’re of a mind to go digging around and trying to pull down higher-quality files then you’ll still usually end up with a sub-perfect product quality-wise, as well as something that will eat up probably a lot of storage space – in short, there are easier and better ways of getting to content than adopting this as a default part of your arsenal…