A few years ago a friend and colleague of mine passed away. This isn’t surprising because he was around my age and, well, I’m hanging on to forty-nine by a margin of mere days, and the further you creep away from the middle-point of your allotted three-score-years-and-ten the more intimate your relationship becomes with the actuarial tables and the inescapable fact of your own, ultimate demise. I mean, I don’t want to be a downer here, but as William Shatner pointed out in 2004, you’re gonna die, and there’s no sense in getting all bent out of shape about it.

Still, that’s not to say that the prudent course of action is to embrace the futility of existence and go gallivanting off toward the great hereafter with an affect of gloom and futility. After all, you may be dead – sure – but there are a few things you can do to make the whole unpleasant business of your departure from this tawdry earthen firmament easier and simpler for you and yours. My wife is an attorney who does a good amount of estate planning work – chiefly laying out the dispersal and disposal of physical goods and financial instruments once the offending party has joined the choir eternal etc. That’s important work in my book, and my side of the street (chiefly composed of the dispersal and disposal of ones and zeroes) kind of pales in comparison.

Still, how said dispersal/disposal can be executed isn’t as cut and dried as we’d like it to be. There’s no simple, one-size-fits-all approach to neatly wrapping up a digital identity. Sometimes that can be dealt with quickly and easily, but other times? Yeah. Not so much.

This is all a roundabout way of getting to the thing that’s annoying me today, to whit: that Twitter keeps trying to tell me that I should check out what my dead friend is up to these days, and it’s low-key upsetting to have this reminder pop up on what is now becoming a semi-regular basis. I mean, I went to the man’s funeral and wore a suit and made awkward conversation with colleagues, and thus I’m pretty confident that I know what he’s up to (i.e., not much). Of course, Twitter doesn’t know that (and is currently tip-toeing around its own mortality), and because my friend’s family don’t have any of his passwords or access to his digital credentials there’s really no easy way of persuading Twitter to quietly put that account on ice, remove it, or generally stop rubbing his now-prolonged lack-of-existence in everyone’s faces.

Last year another friend of mine died in a car wreck, leaving behind a broken iPhone (wiped by having the wrong passcode entered too many times by person or persons unknown), a locked PC, an Android tablet, and an unknown AppleID password. I was able to help his family recover most of his data (including passwords), although the process was best described as fiendish and torturous – a teetering edifice of linked accounts and two-factor codes assembled in the right order to get to a point where his Apple ID could be unlocked, read, his data exported and then finally wound up. Apple was less than helpful – while they have procedures in place to dissolve Apple IDs and iCloud accounts those procedures involve sending them proof of death in the form of a death certificate, power of attorney, and possibly letters testamentary, as well as many weeks of waiting.

Meanwhile, emails go unanswered, bills go unpaid, services get shut off. In my dearly departed chum’s case, he had a thriving seasonal business with a lot of customers who had no idea what had happened to him or their money, resulting in an ever-growing snowball of angry phone calls that went to inaccessible voicemail and stern notes from attorneys along the lines of we’ll-see-you-in-court – which, considering his physical and metaphysical disposition at the time, would have been really quite an achievement.

The thing is that there are few if any widely-established and accepted methodologies that are recommended and deployed for dealing with what happens to a person’s data after they die. The people themselves? There’s religion and the legal system for that, but their data? That’s trickier. In the past I’ve suggested to clients that a viable option is to write a letter; leave a note for your loved one(s), laying out your accounts, passwords, and optionally printing out two-factor recovery codes for services that offer that as an option. It’s an approach that’s not without serious issues – for one thing, you have to keep that letter updated every time you change a password, and for another there’s an inherent security issue in writing down the keys to your entire digital life on a piece of paper and leaving that lying around your house. It can get damaged, or fall into the wrong hands, or just plain be overlooked. If you have the means and the inclination, you can put that letter into a safe deposit box – and I know a few folks who’ve done this. The caveat to that is that your bank or financial institution of choice is probably only going to give your heirs or survivors access to that after probate has been all tied up (which can take… a while), so you should make sure that at least one other person is authorized to open that box.

Tech companies traditionally do not care particularly about these kinds of problems. Dead users are, after all, still users – that six months you spend trying to cancel your loved ones’ account? That’s six months of income requiring zero work or expenditure of resources on their part. Look, I get it; it’s an ugly and cynical thing to have to write that, but it’s nevertheless the truth of the matter. We’re used to tech being aspirational and enlightening, but at the end of the day these are commercial enterprises that talk a good line about Not Being Evil or Thinking Different but don’t necessarily take that kind of thing as a mission statement. There’s no point getting bent out of shape about that, but it’s important to remember that ultimately most large tech companies regard their users as a monetized commodity – and that’s okay, because to cut a long story short That Is How We Can Have Nice Things.

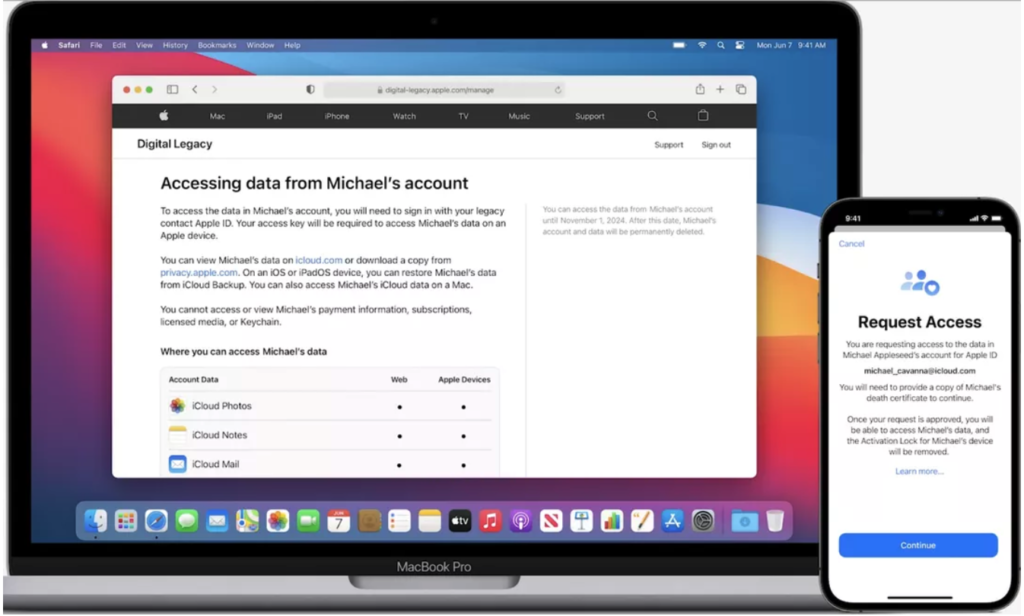

Apple at least has a tool to streamline the process of unwinding the affairs of the departed, allowing you to create what they’re calling a Digital Legacy; a way for your surviving nearest and dearest to unlock your Apple ID provided that you – the dearly departed – have allowed specific people access to your Apple ID and that they have a copy of your death certificate. With that in hand, they’ll be able to recover pretty much everything except keychain data and payment information. Further, Activation Lock will be disabled for your devices.

None of this is terribly exciting. Not compared to some other tentpole features of Apple’s products. Digital Legacy isn’t what you’d call glamorous or cool – and it’s nothing new; it’s more a streamlining of an existing process, designed to make something frustrating and annoying a little easier at a time when people have reduced bandwidth for frustrations and annoyances. Further, it doesn’t give access to password or keychain data, which – if you’re a hardcore keychain fan – might cause some headaches.

The problem with being a person who professionally handles disasters is that folks in my field skew toward the worst-case scenario (after all, shockingly few people call IT consultants for a chat because everything is running perfectly). In an age where so much of our lives ends up being insubstantial data we become – in effect – custodians of our own and other peoples’ legacies. The tools we have at hand for that kind of purpose are imperfect at best, and just to be clear, I don’t think that something like Digital Legacy is a perfect tool. It is, however, a huge improvement over anything else currently extant and also probably good enough for a lot of people.

After all, the things we leave behind that are of the most value aren’t passwords and numbers and credentials. Sure, those are handy to have if you’re tidying up your loved ones’ affairs, but the absence of that kind of information is mostly just annoying and inconvenient. Digital Legacy doesn’t service that kind of need, but where it excels is in allowing you access to personal data, which is the kind of data that your loved ones really want access to – photos, documents and email.