I like a nice, useful maxim. A pithy truth; something sharp and memorable and useful. They’re the building blocks of arguments and add an air of finality to proclamations.

This morning I woke up to a very polite note in my inbox from a friend of mine, linking me to some incredibly specious research by a company called Square X Labs who had demonstrated – with moderate fanfare – an apparent gaping flaw in Passkeys, leading to the conclusion that while the technology had promise it had inherent, terrible flaws that make it less than ready for prime time. This study – and its attendant demonstration – are, not to put too fine a word on it… well. I’m sure the good people at Square X are all very intelligent and industrious, so I’ll be generous and say that their conclusions are muddled, and not that they’re profoundly shoehorned into a world view that serves their overarching interest of selling security services for web browsers.

A less than generous take would be that this is a company that sells fire extinguishers in the lobby of a crowded movie theater, and that when they start yelling “Fire” while you’re in the second reel of “Freakier Friday” then you might want to pause and assess whether their motives are – just possibly – not self-serving.

This was the maxim I was going for. The whole fire-extinguisher-salesman thing. Yes, I know, it needs polishing. I’m workshopping some ideas. I’ll get there.

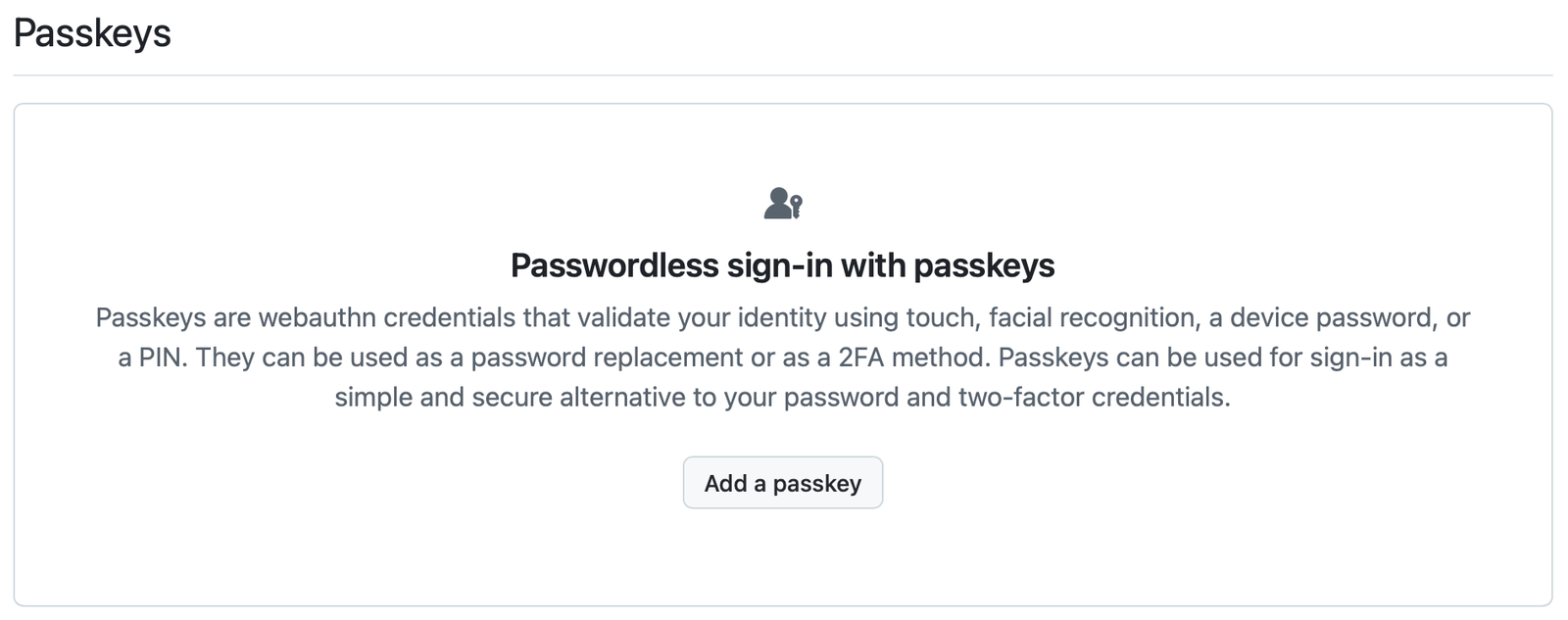

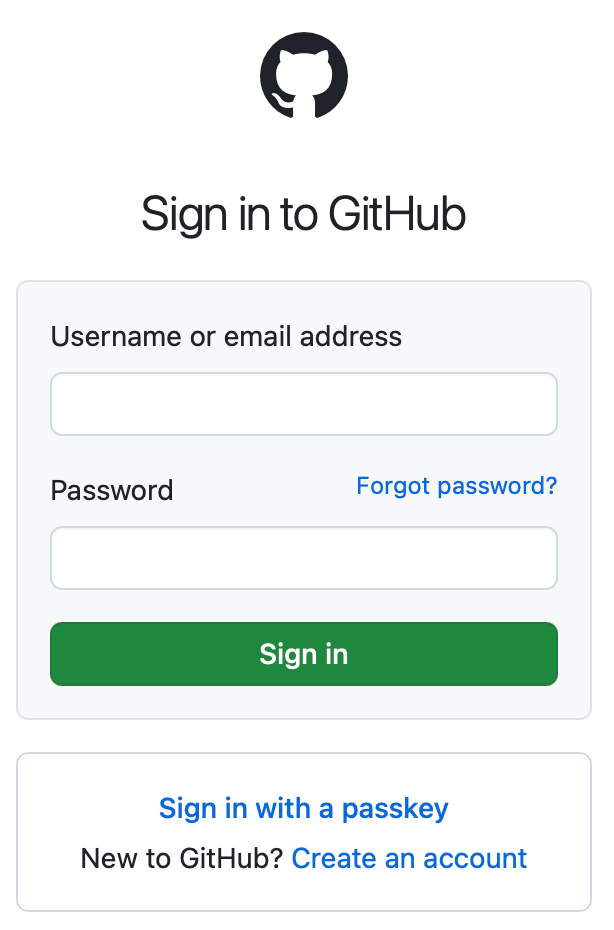

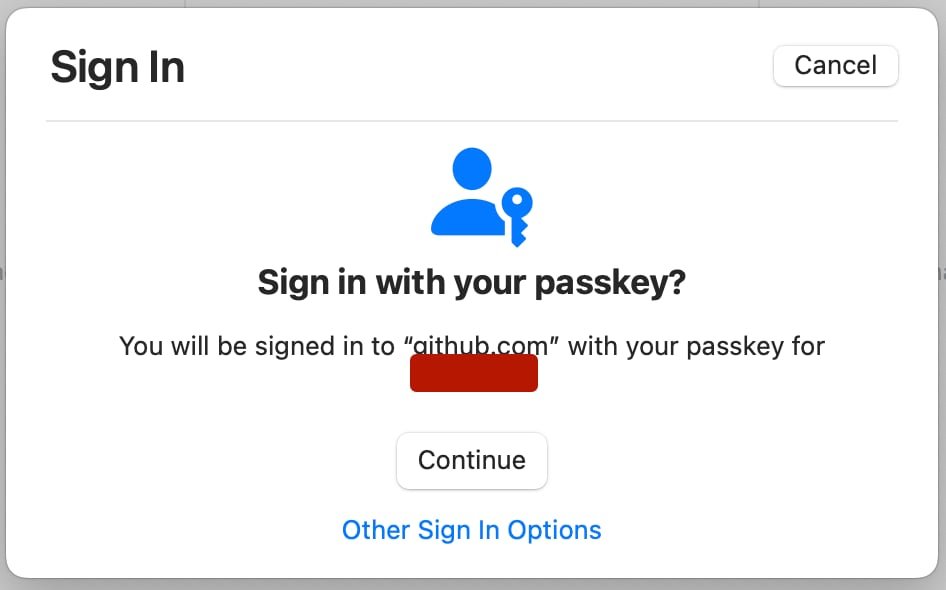

In a very, very simple nutshell, here’s how Passkeys work:

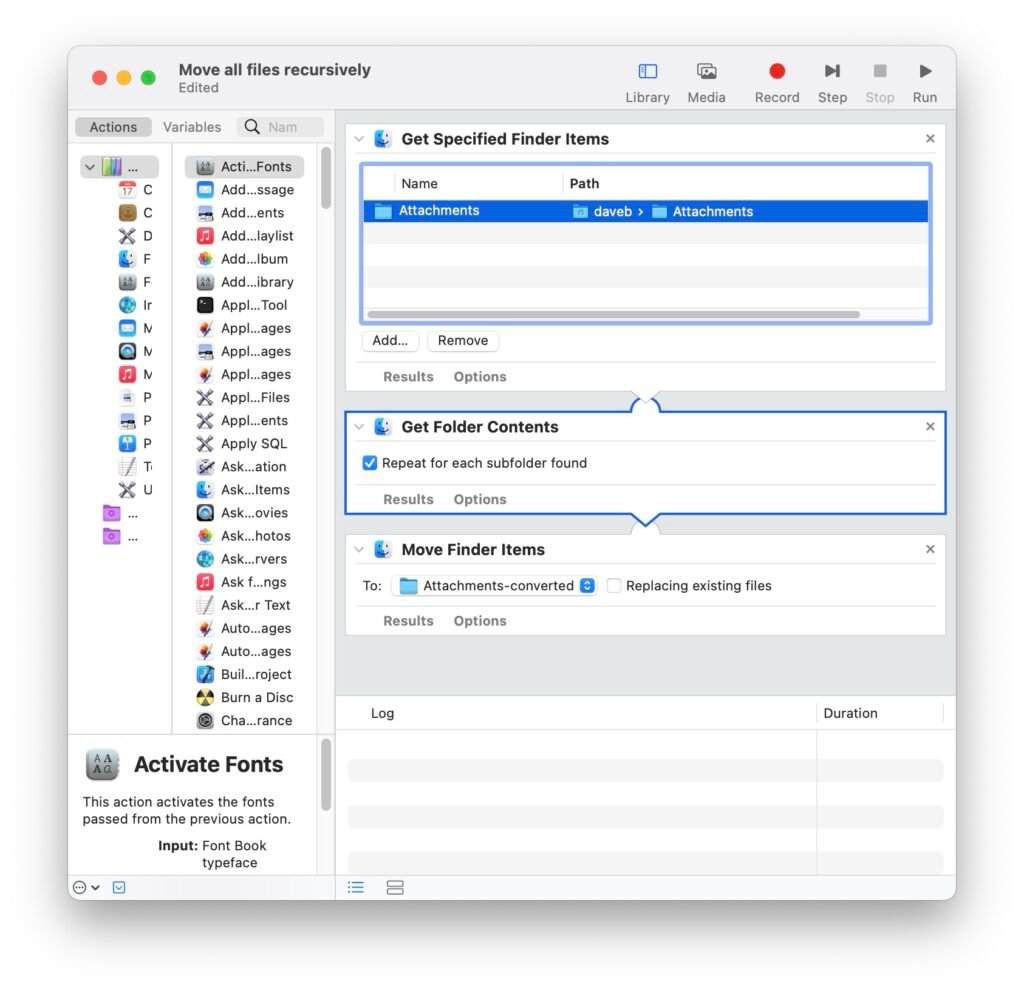

- Passkeys work by generating a cryptographically strong (read “realistically unbreakable by modern cryptographic technologies) set of two keys – a Private key and a Public key.

- You – the user – supply Face/TouchID as a component used to create those keys, making them unique.

- Your computer actually generates those keys by taking input from you and your fingerprints/entrancing facial features, then stores the Private key.

- The Public key goes to the Server of the service you’re authenticating too, so that essentially your computer and the server at the other end each have an individual piece of code that’s useless by itself and only works to do anything when it’s paired with the other piece.

- When you go to access that server through a web browser, that web browser talks to both your computer and the server and generally handles the business of making sure that everyone gets the key that they need.

This is all very ingenious and works just fine, provided that nobody tampers with the process and does something to the one component in the above example that actually handles setting things up and telling both your computer and the server to exchange their keys. That part being the web browser, which, hey, whaddya know? Is sort of the crux of their entire, silly argument.

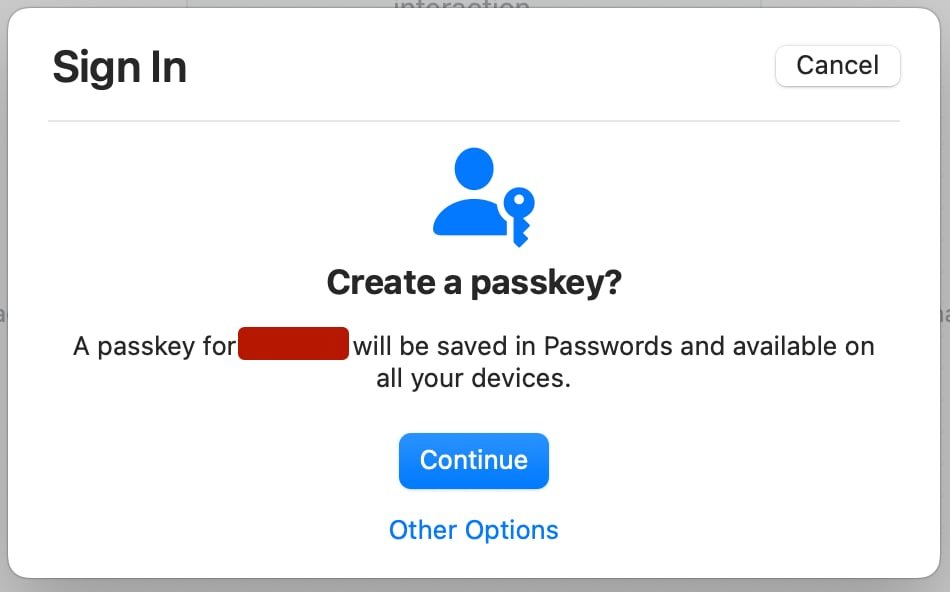

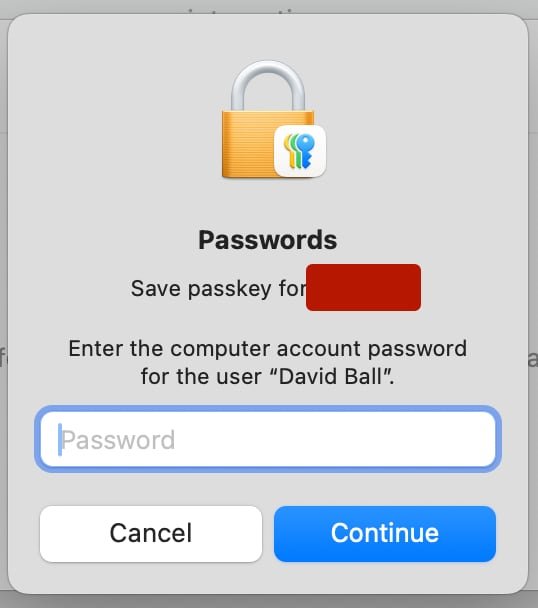

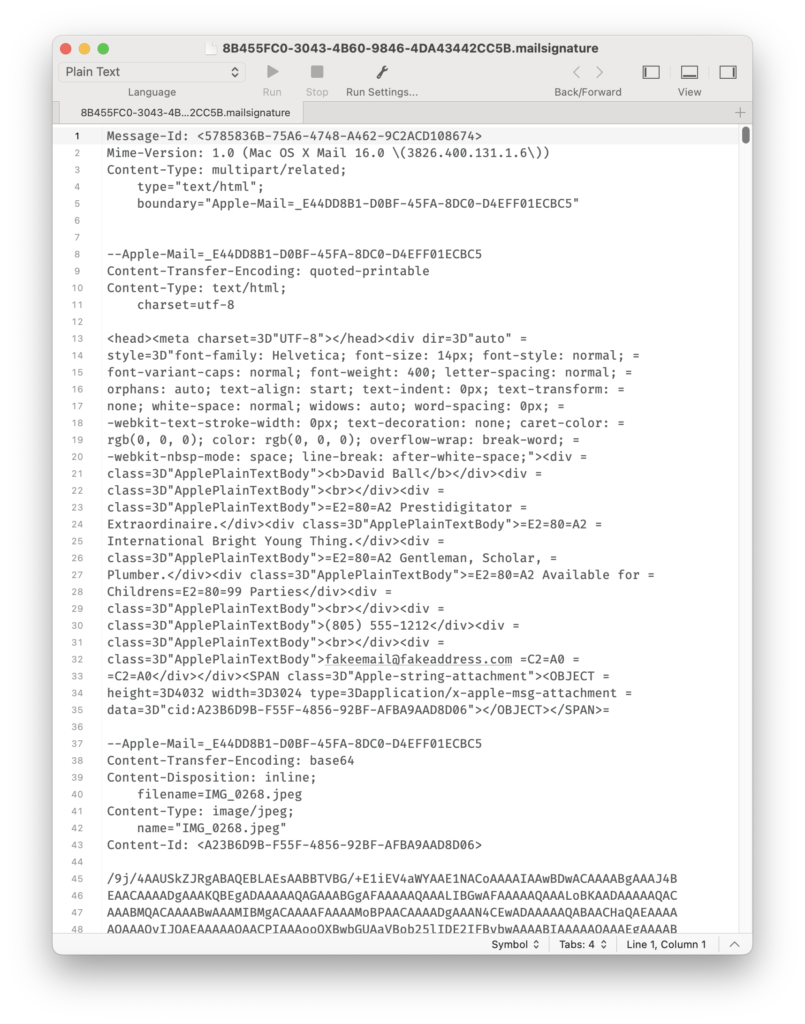

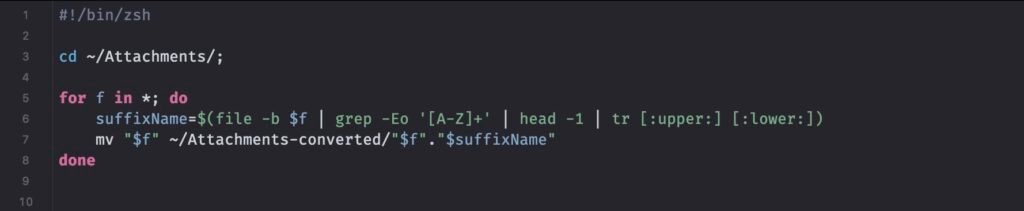

By creating a browser extension that sneaks in to the setup and use of keys – and then by installing that browser extension on your computer through social engineering (bolded/italicized for emphasis) it is possible to put a man in the middle of both the creation and use of a passkey, turning the process into this:

- I want to make a passkey, so open my browser with its installed illicit browser extension.

- The server I’m trying to make a passkey with tells the browser that it’s time to tell the computer to create a pair of cryptographic keys.

- The extension jumps in there and makes its own set of keys. It also sends a call to part of the OS to make it pop up a window so that you can put in your FaceID/TouchID, but this is really just to make you – the end user – think that everything is okay, and the extension ignores that data.

- The extension sends a Public Key to the server you’re trying to get to, and keeps the Private key to itself so that as long as you’re using that browser/browser extension then the server will be able to see your Private Key, match it with its Public Key, and you’ll be able to go and pay your electricity bill via online banking and be reasonable assured that interaction is safe.

- Meanwhile, the browser extension is secretly sending your Private Key to its evil Criminal Overlord Masters so that they, too, can go and log in to your bank and drain your accounts and generally ruin you.

None of what they’re proposing is impossible. Nor, really, technically very complicated. But while they’re positioning this as an inherent flaw in the Passkeys system, I’d like to break out another maxim:

Hackers don’t hack. They log in.

That part I italicized earlier? That’s the part to pay attention to. If someone has created a browser extension explicitly designed to intercept the creation and use of Passkeys, they haven’t obviated Passkeys as a technology. If someone gets you to install that extension on your computer then that’s bad, sure, but it’s not indicative of a flaw in the Passkeys process. What they’ve done, simply speaking, is the equivalent of getting you to tell them your bank account details and then when you’re not looking, cleaning you out. They’re not hacking your accounts; they’re taking the passwords that you gave them when you cheerfully circumvented all the protections that you were afforded, and then they’re using them to log in and rob you.

So. What’s the takeaway here? Well, it’s not fun and it’s not exciting, but it is valuable, and it needs to be said and said clearly – Don’t Install Things On Your Computer That You Don’t Trust. Also? Don’t believe everything you read, particularly when the people who are telling you things are also selling you things…