One of the enjoyable things about this whole Global Pandemic Jamboree has been that – like the great bulk of my peers – I’ve had a chance to contemplate the greater truths of life and ponder the big questions about the fleeting nature of time and the fragility of man. I’ve also had a lot of time to sort through a lot of things, and not in the incorporeal emotional self-actualization sort of way, but in the “I-have-a-pile-of-dead-gear” kind of way. Which, if you’re weighing those two options, is a lot more fun and involves slightly less weeping.

Specifically, I had five dead Mac minis in various states of decay and destruction; all of them having been torn down and worked on and declared unfixable in a reasonable economic sense by clients, and all in the big box of broken stuff that I run to eWaste recycling every few months. Now, when someone hands me a dead computer and tells me that they don’t want to ever see it again I do the sensible, grown-up and professional thing of immediately destroying the hard drive with a hammer and drill so that any data on the thing is irretrievable, which generally leaves me with about 90% of a computer that most likely has some terminal issue (either diagnosed or undiagnosed.) Bad RAM. Bad logic board. Torn cabling, damaged fans, iffy-or burned out power supplies. Given enough time, one could go through all those machines and work out what was wrong with each and possibly – given even more time – cobble them together into some FrankenMac.

Well, of late I seem for some incalculable reason to have time to burn, so I did exactly that. Behold my creation! Look upon it and weep:

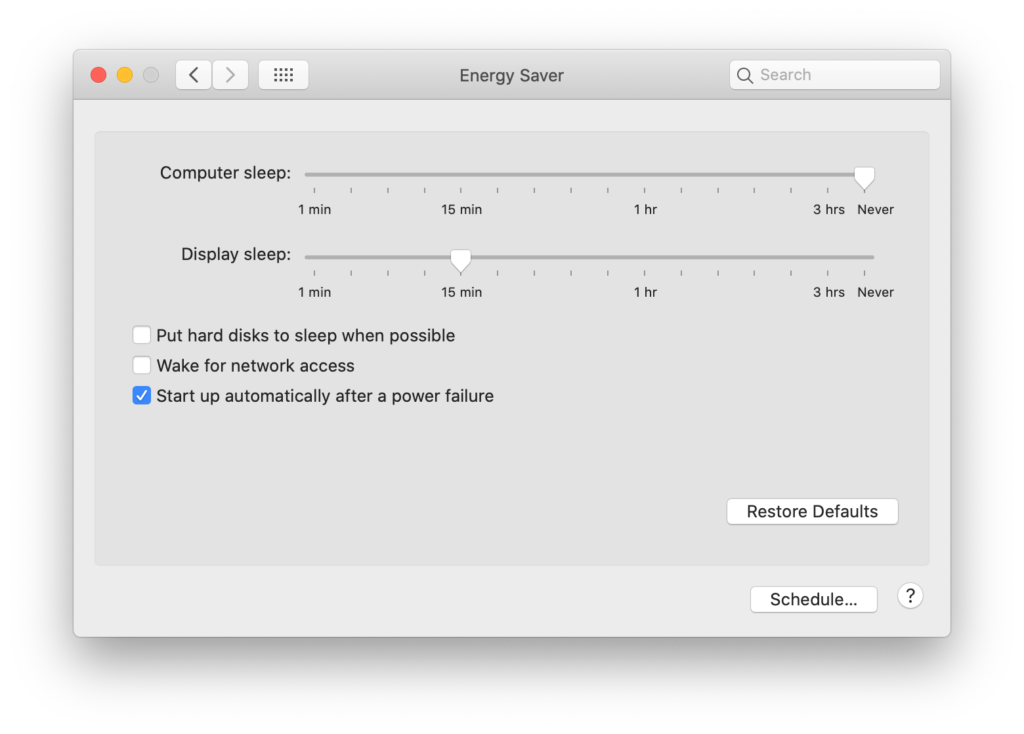

Okay, well it’s not that impressive. I feel I rather hyped it up, and that’s on me. But it thinks that it’s a 2010 Mac mini with a 2.4Ghz Core 2 Duo, 8GB RAM and an SSD, and all-in-all it’s a decent-if-unremarkable box that I leave hooked up to the stereo in my garage and also use to feed print jobs to my 3D printer.

I like to 3D print at night because I have no patience and if something’s going to take 9 hours to reach fruition then I’d rather as much of that as possible take place while I am dead to the world. The thing is, however, that at night time the garage is really, really cold and drafty, and also I saw a rat in there one time and there might also be spooky ghosts, so I don’t generally feel excited about sitting around in there at night and setting up print jobs. I’d far rather just push the files to the thing and screen share in so I can make the thing run overnight and go check on my prints the following morning when it’s warm and the rats are sleeping and the chances of seeing sets of macabre, incorporeal twins holding hands and telling me I’m going to play with them forever are substantially lower. Also, the Mac mini is precariously perched on a shelf and prone to falling down if I fuss with the USB ports. I mean, look at that picture – it’s basically held in place by two sharpies and a certain amount of luck.

I have the thing set up with key-based SSH and a static IP, and because I do a fair amount of fussing around and tweaking of 3D print files I wanted to be able to just have the print folder on my Mac Pro (in my home office, warm, no rats, only occasionally haunted by a cat who sits in my good chair and won’t move) synchronize with the print folder on the FrankenMini, which meant setting up rsync.

rsync and I are old friends and go back a ways; right back to the earlier days of OS X, pre-Time Machine. Backing up a Mac back then was usually accomplished with backup software like Retrospect, but while Retrospect was fine at what it did I ran into a few situations where one didn’t so much need a specialized software backup as much as one needed to shove a bunch of files from point A to point B and have that operation not copy over anything that hadn’t changed.

rsync was simple, elegant and fast. Simply, you feed rsync a folder/directory/file and then it synchronizes that input with another folder/directory/file – either locally on the same computer or with another computer. When you fire up rsync to have it sync to another computer it opens up an SSH session and fires up another rsync instance on that remote machine. The two instances of rsync compare notes, calculating hashes for each file, and if the hashes don’t match then the appropriate file is copied to the appropriate machine.

There are a couple of gotchas that you have to bear in mind, though. The big one is that when you copy a file from one Mac to another then the file creation date on arrival on the remote Mac changes to the modification date of the file; in plain English, if it’s April 28th and you copy over a file last modified on April 25th, then when you look at the file that’s been copied to the remote Mac it shows the file creation data as April 28th. This isn’t ideal, but can be fixed by invoking archive mode using the -a flag.

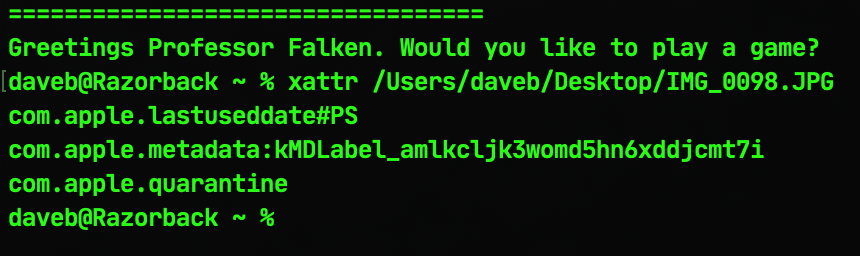

The second problem is that rsync neglects to copy over extended attributes and resource forks. Extended attributes are bits of metadata in the file that can contain things like quarantine info, label information and so on. You can take a look at the extended attributes of a file by invoking the xattr command thus:

Resource forks are a different issue – and one that’s increasingly become less pressing as time goes by now that they’ve been effectively deprecated in macOS, but both extended attributes and resource fork problems can be resolved by invoking the -E flag.

So, to business. The FrankenMini sits at IP address 10.0.0.64 and already has SSH enabled via the Sharing prefpane. If I have a folder called “3D_Print_Files” in my ~/Documents folder then the command would look like this:

rsync -HaE "/Users/daveb/Documents/3D_Print_Files/" dave@10.0.0.64:"/Users/dave/Documents/3D_Print_Files"

So, what’s happening there? Well we’re invoking rsync with the -H (preserve hard links), -a (archive mode to preserve date and time and other flags) and -E (extended attributes and resource forks) options, then pointing to the source folder that the initial sync is running from (in this case, "/Users/daveb/Documents/3D_Print_Files/" on my Mac Pro in my non-haunted and non-rat-infested office). The destination folder is called through an SSH session by feeding it the username of an account and the IP address of the remote machine (dave@10.0.0.64), and then the location of the destination that you’ll be copying the data to ("/Users/Dave/Documents/3D_Print_Files")

The net result will be that you’ll end up copying the contents of the source folder to the destination folder, ignoring files that have not been updated. And this is all well and good, but what do you do if you want to actually make the two folders sync with each other rather than just copying source to destination? All that’s required is to switch the command around and append it to the first command, like so:

rsync -HaE "/Users/daveb/Documents/3D_Print_Files/" dave@10.0.0.64:"/Users/dave/Documents/3D_Print_Files" && rsync -HaE dave@10.0.0.64:"/Users/dave/Documents/3D_Print_Files/" "/Users/daveb/Documents/3D_Print_Files"

This is, admittedly, rather a mouthful, but you can easily make a command alias out of it by throwing it into your .profile/.zprofile, which should simplify matters considerably.

This is, in essence, a pretty simple trick, but all talk of rats and ghosts aside it’s a remarkably simple and easy way of replicating and synchronizing potentially vast amounts of data over both a local and wide network. I wouldn’t suggest using it over the internet without some kind of encryption (either certificate-based or an honest-to-goodness VPN), though, but if either of those is an option then rsync can be a pretty versatile tool in the arsenal of anyone who isn’t going out much these days…